Fot. Wilfried Hösl

Named the “Most Promising Singer of the Year” in 2005, Pavol Breslik is one of the most popular opera singers in the world today. He won the prestigious Antonín-Dvořák Competition in 2000 and took part in the 2017 opening ceremony of the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg. He has performed on the world’s greatest stages, from the Metropolitan Opera New York to Covent Garden, Glyndebourne, the Vienna State Opera, the Salzburg Festival and the BBC Proms at the Royal Albert Hall. After three months in lockdown, due to the global coronavirus pandemic, Breslik made a triumphant return to the Bayerishe Staatsoper in June performing Janáček’s song cycle The Diary of One Who Disappeared. Jansson J. Antmann caught up with the tenor during rehearsals for Die Csárdásfürstin, opening in September at the Zürich Opera House.

Text: Jansson J. Antmann

Throughout your career, you have performed leading roles in Mozart’s operas at theatres and festivals around the world. You have said that singing Mozart is the ultimate way to learn technique.

Wolfgang taught me a lot and I’m so grateful I began my career singing his works. A singer must have perfect technique. Without it you’ll damage your voice. Mozart was such a complex composer and his vocal pieces are utter perfection. He is the best example of why a healthy voice is so important. There is a purity of sound; a legato that demands technical brilliance. In my opinion, every singer should sing Mozart. Even Wagnerian singers do.

You keep returning to Mozart’s operas and will perform the role of Belmonte in Die Entführung aus dem Serail at the Bayerishe Staatsoper in June next year. Tamino in The Magic Flute is another role you perform again and again.

Tamino was actually my second Mozart role. The first was Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni at the State Opera in Prague. I was 21 at the time. Three years later I sang Tamino at Glyndebourne. Now I’m 41 and the role is still in my repertoire. Singing Mozart is like taking your car to be serviced. With age you sing heavier roles, like Edgardo in Lucia di Lamermoor, Gennaro in Lucrezia Borgia, Nadir in The Pearlfishers or Faust. After singing these parts, I always like to go back and perform a role like Tamino, because it’s good for the voice. Another one is Belmonte with its coloratura passages, which keep the voice healthy and light.

In 2017 you performed the world premiere of Wolfgang Rihm’s Reminiszenz at the long-awaited grand opening of the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg. Some of the dignitaries present included German President Joachim Gauck, Chancellor Angela Merkel, Mayor of Hamburg Olaf Scholz, and the architect Jacques Herzog. What do you remember of that very special occasion?

It always makes me happy when people mention the Elbphilharmonie, and deep down in my heart I think how lucky I was to perform at the opening. Reminiszenz had been written for Jonas Kaufmann, but he fell ill and I had to learn it and stand in for him. I enjoyed it and have performed the piece since.

Given the success of your performances of Reminiszenz at venues such as the Philharmonie de Paris in 2017 and the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam the following year, can we look forward to seeing you perform works by other modern composers?

When it comes to contemporary music, I’m not a huge fan. Nowadays composers don’t seem to be able to write especially well for the voice. It’s not the same as writing instrumental music, which has intervals that require you to jump huge scales, while you try to find the right note. I performed in Berg’s Lulu in Salzburg. It’s a beautiful piece, but it’s incredibly difficult. Of all the works I’ve performed, it took me the longest time to learn. I did it once, and that was enough. Never again! That’s not to say I’m a lazy tenor, who doesn’t want to learn new things. On the contrary. I’m very happy to, but composers need to learn more about how the human voice works. I would like to sing for many years to come, and I don’t want to pretend to be a prince and perform Tamino for the rest of my life. However, if I want to still be singing when I’m 65, I need pieces that are healthy for the voice.

The operetta is generally considered a form that places less strain on a singer, and you have enjoyed performing in various titles over the years. Is it escapism?

I like operetta a lot. Although the vocal parts are not very demanding in terms of the range required, you still have high notes, but there’s more freedom of interpretation. If you have a great conductor with whom you can connect, you can have a lot of fun making music on stage.

Even so, it can’t be as easy as it sounds.

Operetta is very easy to listen to, but not very easy to perform and sing. You need to dance and act, which is especially challenging for me, because I hate dialogue. People from the Slavic regions like me are very throaty. We don’t speak like people in Italy, where everything is positioned nice and high. Therefore, it’s difficult to find a balance between my speaking voice and singing voice. The dialogue needs to be clearly pronounced and projected and I don’t want to sound like Mickey Mouse when I talk. Nevertheless, the melodies by Lehar and Kálmán are so beautiful and make me happy.

In 2018 you had to meet the challenge of combining song and dance, when you were invited to perform at the Vienna Opera Ball at the Wiener Staatsoper, which was attended by over five-thousand guests and watched by a television audience of approximately 2,5 million people. How did you enjoy that experience?

I was very pleased and honoured to be invited to open the Opera Ball in Vienna. It’s something that can only happen once or twice in a lifetime. After all, it is the most famous ball in the world. I have to admit it was quite stressful, because during the general rehearsal I realized I couldn’t hear the orchestra and the musicians couldn’t hear me. What’s more, the conductor couldn’t see me, even though he had to respond to what I was doing in the auditorium. I don’t like using a microphone, but in this case, there was no other way. I sang “Ah, lève toi soleil” from Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette and “Lippen schweigen” from Lehar’s The Merry Widow with Valentina Naforniță. The dancefloor was extremely crowded, but I danced for 10 minutes and it was a wonderful, if somewhat crazy experience.

You are now rehearsing Kálmán’s Die Csárdásfürstin at the Zürich Opera House in a new production by German theatre and opera director Jan Philipp Gloger. The operetta had its premiere in Vienna in 1915 andthe libretto reflects the political climate of the day. Ending with the protagonists’ declaration of love as the rest of the world descends into madness, the work would seem a timely inclusion in the repertoire.

It’s such a great piece and I’m looking forward to performing the role of Edwin with Annette Dasch as Sylva. In 2014, I also performed the role of Boni in the same piece with Anna Netrebko in Dresden. It was the New Year’s Eve concert conducted by Christian Thielemann at the Semperoper, which was a lot of fun. This new production in Zürich was supposed to open at the end of April and run through May this year, but of course it was postponed because of the coronavirus. We are now scheduled to open on 25 September.

You are in high demand. Although vocal stamina is paramount, the physical and emotional demands placed on a performing artist are gruelling. What does your daily routine look like on a day you’re performing?

It’s not an easy life, but I like it. Of course, I couldn’t do it without the support of my family, my friends, and my manager Rita Schütz. Without them, none of this would be possible. On a performance day, I wake up and go for a walk with my dog, Mia. I feed her and make sure she’s happy, because when my dog is happy, I’m happy. I have a beautiful Weimaraner. She is very intelligent and has such beautiful eyes, which can be difficult, because it means she often gets what she wants. After that, I warm up and find my voice. You never know if it’s there, especially if you’re a tenor. Once I’ve warmed up, I’ll have something to eat and start preparing for the performance. I put on my make-up and my costume, at which point I start to feel nervous. I always get butterflies. The first minutes on stage are the most unpleasant, but once the orchestra starts and I’ve sung a few bars, the nerves are gone. From that point on, I’m caught up in the story. After the performance, the hardest thing is coming down and letting go of the character I’ve played. However, once I’ve closed the door of my apartment and I’m alone, I leave the role behind and I’m Pavol once again. And then there’s Mia, who needs to be fed and go for a walk. She helps me come down too.

You seem to be very down-to-earth and you haven’t lost touch with your roots. Do you think that’s why you’ve made a name for yourself as an exponent of the Slavic repertoire?

I’m from Slovakia, so I grew up with Slavic music – Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky, Dvořák, Smetana, as well as Slovakia’s own Eugen Suchoň and Mikuláš Schneider -Trnavský, whose music I featured on my first solo CD. As a child I listened to Rusalka and I could even sing every part when I was at school. You will find the heart and soul of the Slavic people in every piece of Slavic art and music. It’s what takes the audience to another world – a world of sad dreams. It’s in the operas and the songs… those amazing, sad songs. That’s not to say we can’t be funny. There are a few humorous works too, but it would seem that people prefer sad stories. The Slavic repertoire is a huge part of my life. It influences my interpretation of the songs I sing. When I perform, I always try to include something from my home country in the program, because I like introducing audiences to something they might not have had the opportunity to encounter before.

Last year you performed the role of Hans in two different productions of Smetana’s quintessential Czech opera The Bartered Bride. Both were sung in German and transported the piece out of its quaint, bucolic setting. One was directed by David Bösch at the Bayerishe Staatsoper in Munich, and the other by Mariame Clément at the Semperoper in Dresden. Was it easy going from one production to another?

The funny thing is that Smetana was actually a German-speaking composer and he originally composed The Bartered Bride with a German libretto. It was subsequently translated into Czech, and that was how I first sang the opera in Bratislava. That was a very funny production. Then I performed in David Bösch’s production in Munich. I love working with David. He’s such an easy-going director and I really like his style. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t want to sound like I preferred David’s production over the one in Dresden, but it uses the original German libretto, whereas the production at the Semperoper uses a newer version. I performed in Dresden right after the season in Munich, and I therefore found it difficult to switch from one German version to another. I had sung the original many times before and it was almost like second nature to me. Suddenly, I was faced with a newer translation – the music was the same, but the words and phrasing were different. Sometimes I’d find myself unsure of what my next line was, or I’d even use words from the original libretto. I was on autopilot and poor Hrachuhí Bassénz, who played Marie, would open her eyes and look up at me as if to say, “that’s not the right version.” I’d need a computer instead of a brain to differentiate between those two libretti. [chuckles]

Putting the challenges of juggling two different versions of the same opera aside, you seem to have no trouble reconciling the various acting and vocal demands of the roles you perform, which is just as well, considering that your repertoire ranges from opera seria and buffa to bel canto, Lieder and the Second Viennese School.

Once upon a time, opera singers were able to stand on stage like a sack of potatoes. Fortunately, those days are over. Nowadays one needs to be the full package. Of course, first and foremost, we are opera singers, but you also need to give the audience something to look at. That’s not to say that you don’t need to take care of your voice. And you must always maintain an open dialogue with your directors, just in case they want you to do something that might threaten the musical integrity or compromise your vocal performance. Singers and directors generally need each other to achieve the finished product, although that can depend on the director. However, a director can’t do it without the singers.

Are you ever apprehensive about the way some directors interpret certain operas?

I don’t want it to seem as though I always prefer traditional or classical productions, but I appreciate a staging that has an inner beauty, a reason and meaning. I like a production that tells a clear story. I’m not overly keen on directors who can’t see the wood for the trees. An opera needs to be considered in its entirety. If one stops to focus on just one mystical or philosophical element, one risks losing sight of the complex structure of the piece and what the composer originally intended.

With such a broad repertoire, do you prefer comedy or tragedy?

It’s nice to have a laugh on stage, but comedy is very difficult. Then again, it’s also difficult to make people cry, even though I think audiences enjoy tragedies more. Just look at how beautiful it is when Violetta dies in La Traviata. I also find that after I’ve done a lot of tragedies, like Lucrezia Borgia, I need something lighter for a change. That said, there’s nothing quite like the wow factor of the final scene in the cemetery in Lucia di Lammermoor. As the orchestra swells and I sing „Tombe degli avi miei” with the chorus behind me, I must admit that’s the kind of death I like.

You’ve previously said how important it is to draw upon one’s genuine emotions when singing the Slavic repertoire. Was this the case when you recorded Leoš Janáček’s 1919 song cycle The Diary of One Who Disappeared, released in February by the Orfeo record label?

It’s a 38-minute journey that takes you from love at first sight to the realisation that you can’t live without that person. I love music and stories that examine the inner conflict between who you were before and after you saw that special someone. You can sense that Janáček composed this cycle in his more mature years, just as you can in his later operas featuring tragic characters like Káťa Kabanová, Jenufa or Emilia Marty in The Makropulos Affair. Through these works, Janáček wanted to show that women are stronger than men and how powerful their destiny can be. That’s why The Diary of One Who Disappeared is somewhat unique, in that it examines a man’s inner feelings and the male condition.

In June, you became one of the first opera singers to return to stage and perform in front of a live audience. What was it like to perform in Friederike Blum’s staging of The Diary of One Who Disappeared at the Bayerische Staatsoper, with Robert Pechanec on piano?

I was very happy to be back on stage. After three months of no singing, no opera and no theatre, I found the semi-staged production very powerful. The auditorium remained empty and the 57 audience members were seated on stage with us. They were so close that you could feel the energy emanating from them. It was an exhilarating and strange experience at the same time and I really hope we can return to a normal way of performing very soon.

In October, you will perform the song cycle again at the Janáček Brno Festival, in a production based entirely on Janáček’s original directorial notes. I was very pleased to see that it is virtually sold out, which makes a mockery of the prejudice held by many governments towards the Arts and the notion that artists aren’t essential to society.

It would be a grey and empty world without artists. After all, what do you do in quarantine? You read a book. And who wrote that book? An author. You listen to music, but first someone had to write it, sing it and perform it. Without artists, there’d be no paintings on our walls. Even the programs we watch on TV employ a whole range of creative skills. It’s all art.

The Arts definitely do enrich our lives, but what do you crave the most?

Physical contact with others. I miss hugging my mother and my friends. The hardest thing is not being with someone you love, or someone vulnerable, because you want to protect them. But it’s necessary.

As a performer, what has been the hardest thing about the lockdown?

I felt really down and useless for the first few weeks. We all did. After so many years on stage, it was like falling into a black hole. When you think of birdsong, only happy birds sing beautifully and so it is for me. Therefore, I tried to avoid thinking about it and, as a result, I didn’t end up missing music that much. Instead, I spent time working in the garden, which was incredibly helpful. I love gardening and digging around in the earth, so it was very healthy for me.

What’s the best part of being a gardener?

There comes a special moment in the late afternoon, when you sit down in the garden to enjoy a glass of wine and look out at all the work you’ve done. You can see the plants growing and the flowers blooming. Even the birds fly down to sing for you. In that moment, you can see another world beyond yours and that’s what counts the most.

I know you enjoy wine-tasting, but what about the young wine at the annual harvest festival?

I can’t drink Burčiak. It makes me ill. It may sound romantic to enjoy a drink in a nice cold wine cellar, but eventually you have to emerge into the sunlight… and then you pass out. [laughs]

I’ve read that you’re a self-confessed foodie.

That’s true. I only have about two or three recipes, but I love cooking… especially for others. As a cook, the greatest reward is seeing your guests leave their plates empty. My love of food is firmly rooted in my childhood. In summer we would get together every weekend in my grandmother’s garden to make goulash. There’s something special about gathering as a family and cooking together. I loved spending time with my grandma in the fields, picking herbs for tea and spices like marjoram and cumin. For me, food always evokes such childhood memories. |

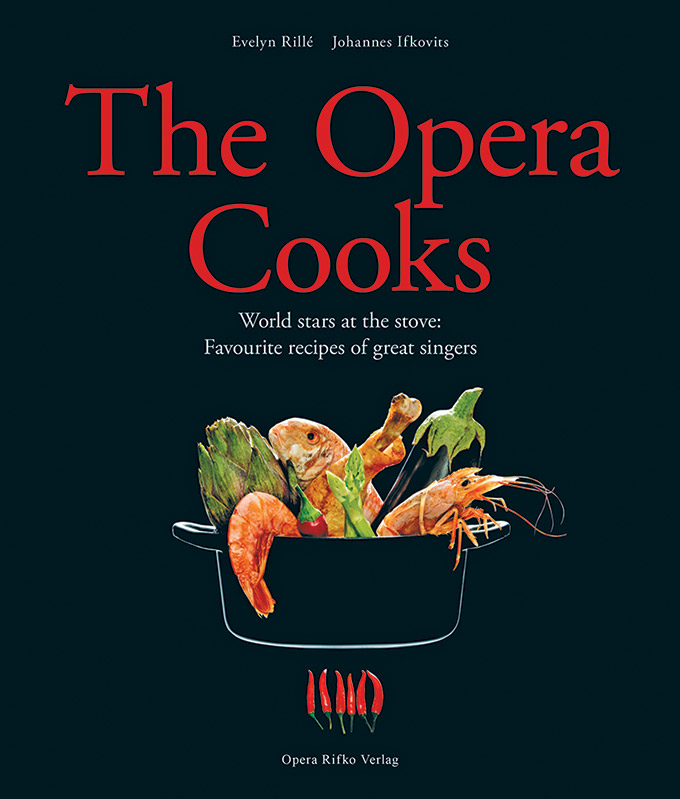

One of Breslik’s favourite dishes – Bryndzové halušky with slow-cooked beef cheeks – will soon be featured in the forthcoming publication The Opera Cooks, alongside recipes from 70 fellow opera stars, including José Carreras, Jonas Kaufmann, Anna Netrebko and Nina Stemme. It will be published by Austria’s Opera Rifko Verlag inOctober this year. Fortunately, La Vie readers don’t have to wait until then, since Pavol Breslik has very kindly shared his recipe with us. “Dobrú chuť!”

One of Breslik’s favourite dishes – Bryndzové halušky with slow-cooked beef cheeks – will soon be featured in the forthcoming publication The Opera Cooks, alongside recipes from 70 fellow opera stars, including José Carreras, Jonas Kaufmann, Anna Netrebko and Nina Stemme. It will be published by Austria’s Opera Rifko Verlag inOctober this year. Fortunately, La Vie readers don’t have to wait until then, since Pavol Breslik has very kindly shared his recipe with us. “Dobrú chuť!”

Bryndzové halušky with slow-cooked beef cheeks

Beef cheeks

Ingredients:

700g beef cheeks

3-4 cloves of garlic

shallot – 1 bulb

3 carrots

3 parsley roots

Tomato paste

Red wine

Salt and pepper

Season the meat with salt and pepper. Melt clarified butter in a frying pan and then slowly sauté the meat. Remove the meat from the pan and add the chopped shallot and garlic, as well as the finely diced carrots and parsley roots. Sauté the ingredients in the same fat as the meat. Return the meat to the frying pan, together with the stewed vegetables. Add the tomato paste and red wine and simmer slowly. When the meat is tender, season once more with salt and pepper.

Bryndzové halušky

Ingredients:

3-4 large potatoes

Plain flour

2 eggs

Salt

Bryndza (if unavailable, substitute with feta or similar sheep’s milk cheese)

Finely grate the potatoes and place into a mixing bowl. Add flour and eggs and stir to make the dough. Add flour and salt as required. Once you have achieved a dough-like batter, boil water in a large pot. Place the dough on a chopping board and, using a knife, cut off dumpling-size chunks and allow them to fall into the boiling water. The batter will sink to the bottom and once the halušky are ready, they will rise to the surface. Remove immediately and strain on the side, while you make the next batch. Be careful not to make too many at once, to avoid them sticking together. Finally, place the halušky in a serving bowl and stir through the bryndza to achieve a creamy consistency. If you are using a substitute cheese, you may want to melt it first. Serve the halušky on a plate and top off with the beef cheeks and sauce.

Recipe and images from DIE OPER KOCHT and THE OPERA COOKS courtesy of OPERA RIFKO VERLAG