With the dawn of the gas-lit era in the 19th Century came the reassuring glow of the pilot light, which ensured we were never plunged into total darkness again. And so, whether it be for practical reasons or out of superstition, a ghost light is always left burning on stage after everyone has left the theatre. It makes perfect sense that a light should remain on to prevent people from falling into the orchestra pit, however the notion of appeasing supernatural forces that haunt a theatre is far more romantic. It is for this reason that ghost lights have become the stuff of lore, with roles many and varied.

Text: Jansson J. Antmann

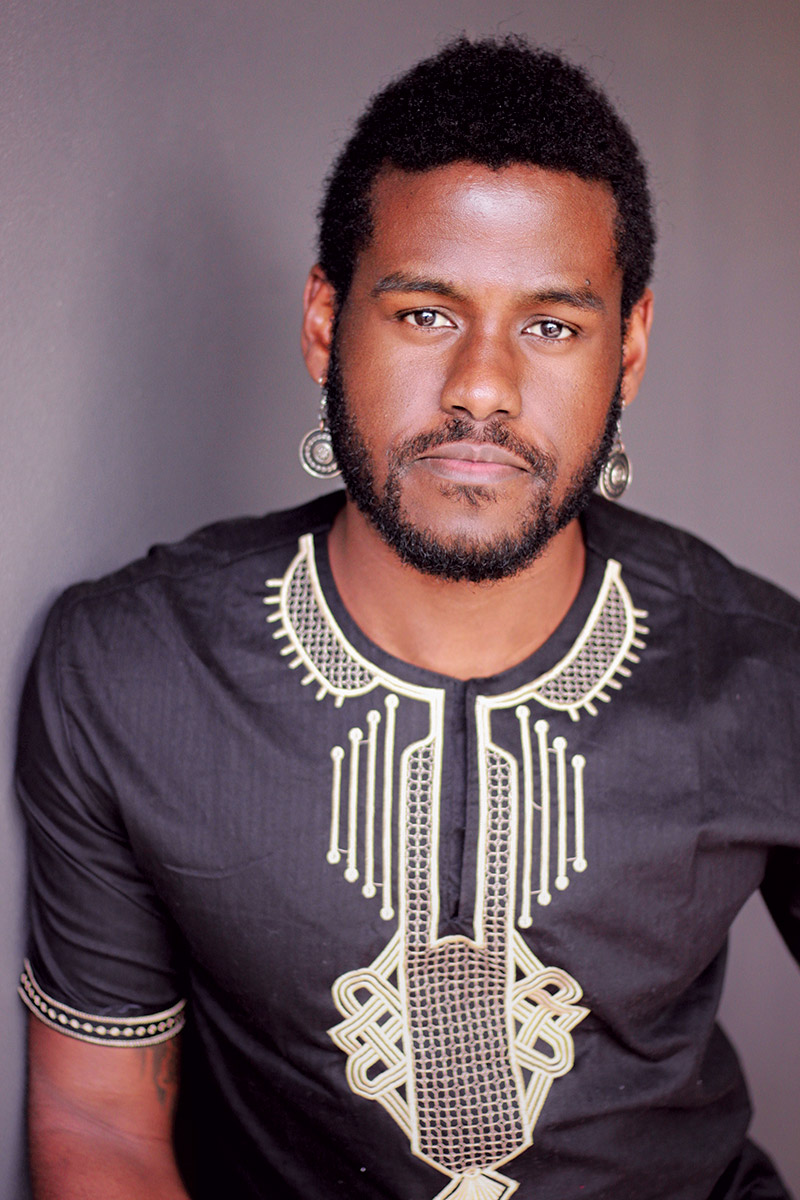

Do they ward off the phantoms that lurk in dark corners of opera houses? Are they portents of epic tales yet to be played out? Or do they provide the light by which theatre ghosts play out their own dramas, safe from prying eyes? Perhaps, in these desolate times of the global pandemic, those ghosts now yearn for an audience. This is the premise of the digital theatre festival Ghost Lights, which brings together famous characters from works by Henrick Ibsen, Luigi Pirandello and William Shakespeare. We find them performing their iconic monologues on the empty stages of different theatres, before coming together in a live performance streamed online from Sydney’s Parade Theatre. While Pirandello may have written Six characters in search of an author, here the characters are in desperate search of an audience. Two of these roles, Nora from A Doll’s House and Hamlet, are performed by students at the National Institute of Dramatic Art in Australia, Ayla Beaufils and Albert Mwangi.

Beaufils and Mwangi have previously performed together in various plays, including as Alma and Reverend Winemiller in Tennessee William’s Summer and Smoke, Arkadina and Sorinin Chekhov’s The Seagull, and the Herald and Jean-Paul Marat in Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade. Beaufils is also an award-winning director, whose debut film in 2016, Good Girls, premiered at the Cannes Short Film Corner. Mwangi is a storyteller, who is passionate about modelling and obsessed with film. In 2017 he got his first taste of Hollywood by working on the motion picture Aquaman.

Ghost Lights is not the only project reanimating empty theatrical stages and bringing the joy of live theatre into homes around the world via the internet.

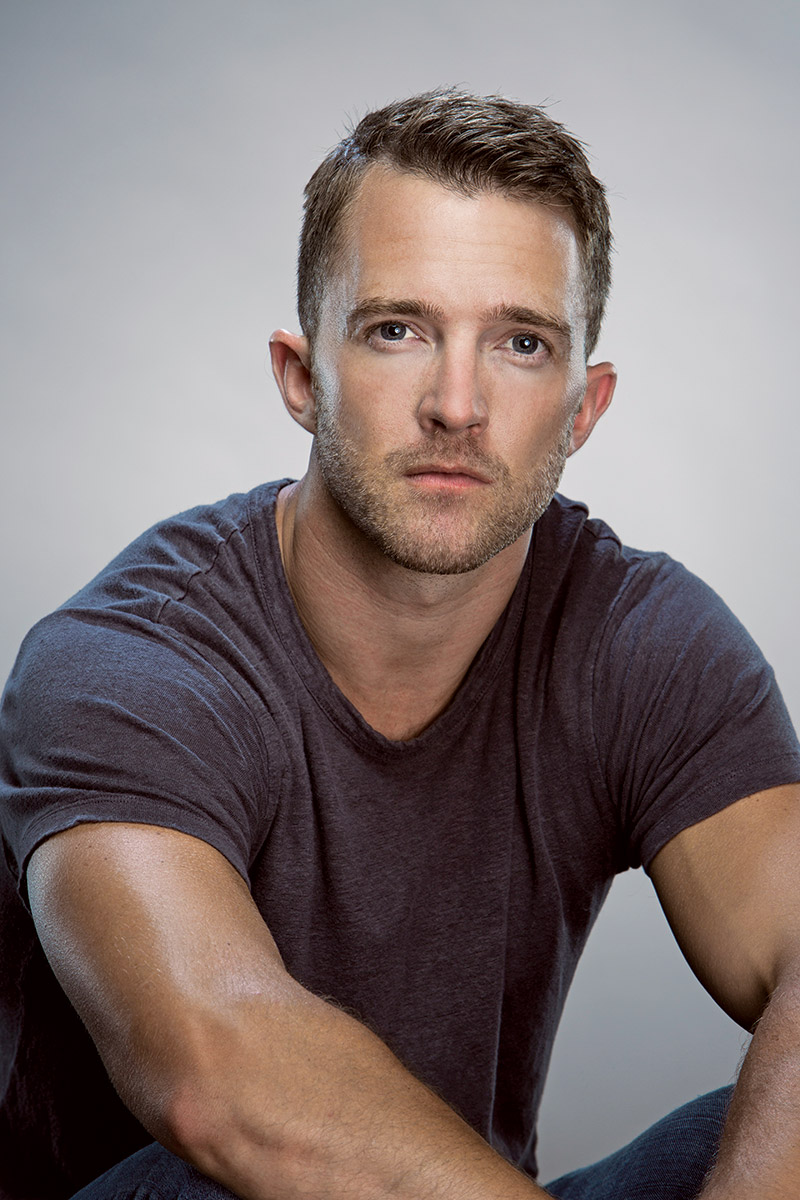

Daniel Assetta, the star of musicals such as CATS and West Side Story, was supposed to perform the role of Al in Darlinghurst Theatre Company’s new production of the legendary musical A CHORUS LINE. After several sold-out previews, the show was postponed on the day of its premiere due to the pandemic. Assetta recorded his cabaret show titled Songs Unsung in the empty theatre only days after the postponement had been announced.

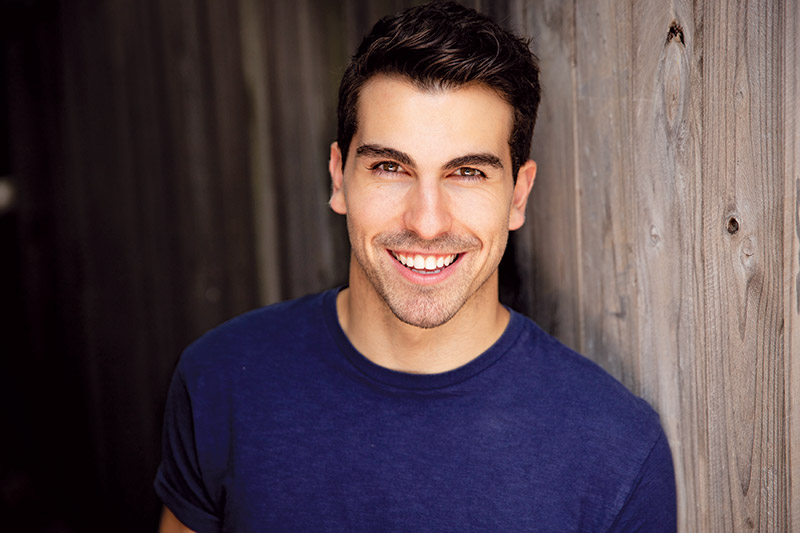

Tim Draxl was also performing in the same production of A Chorus Line in the role of Zach, which was immortalized in the film adaptation by Michael Douglas. An internationally renowned star of theatre, television and cabaret, Draxl was invited to perform his one-man show as part of the Sydney Opera House Digital Season, on the stage of the Dame Joan Sutherland Theatre.

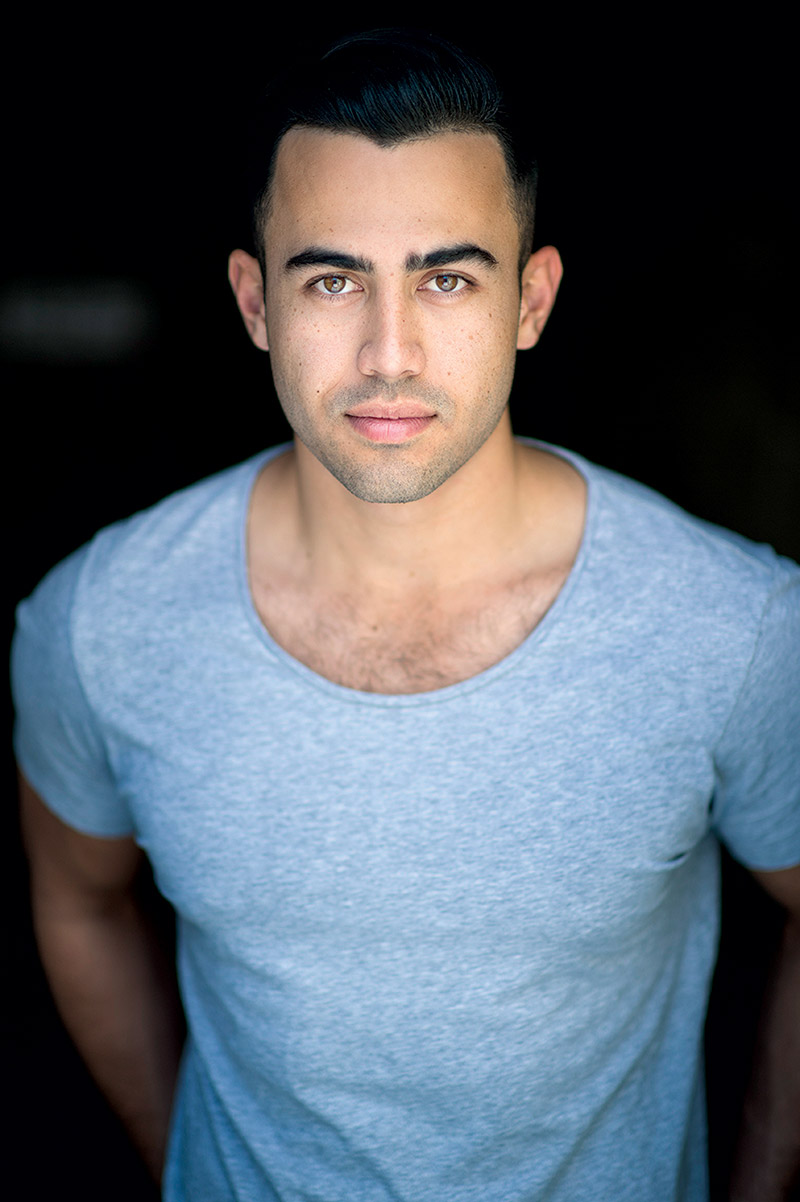

Sean Sinclair was halfway through a tour of North America, as part of the internationally renowned tap-dancing ensemble ‘The Tap Pack’, when the pandemic brought about the cancellation of all remaining performances. Sinclair was forced into quarantine before returning to Australia. Once safely back, the ‘The Tap Pack’ was also invited to perform at the Sydney Opera House and the show was streamed live to a global audience. All five performers spoke to us about their impressions of performing before an empty audience. The interviews offered an insight into the intrinsic bond between a performer and the audience, and also act as a valuable record of a troubling period in theatrical history that will hopefully soon end and never be repeated.

What did you expect it would feel like and how did that compare with what you felt at the time?

Daniel Assetta: Before filming, I was so focused on the preparations that I forgot it was going to be a completely different experience. When we were all set up and ready to start, I had a moment where I thought to myself, ‘Why am I so nervous?’ After so many years of performing live, I guess it seemed strange that the show would be captured and screened at a later date. Obviously, I got a lot of joy from the opportunity, especially during these times, but it was still a very unusual feeling.

Ayla Beaufils: As an actor onstage, I underestimated how inspiring it is to feel the energy of the audience. Usually you can feel, see and hear the audience’s response; their laughter, tears or how they are moved by what they are watching. There’s something very strange about performing in a world of comedy or farce without direct and immediate feedback from the audience. You simply have to trust that you’ve done the work.

Tim Draxl: My first notion of performing in an empty theatre was highly romanticised – the singer steps into the spotlight and belts out a showstopper like never before, free of the pressures of having a live audience. However, the reality was more akin to singing in a vacuum. When you perform in front of a live audience there’s an energy exchange, a silent conversation and the applause spurs you on. It also gives you a moment of repose to collect your thoughts and move into the next song with new intention. Without it, it felt rather like running a marathon. When I was in the throes of a song it was fine. I was caught up in the emotion, and the thrill of performing again took over. However, finishing a song and going straight onto the next one was what I imagine it must feel like when an audience doesn’t clap or respond in any way. It was a new discipline and I was grateful for my years in front of the TV cameras, which I think held me in good stead.

Albert Mwangi: To be honest, I didn’t really think about the impact of performing in front of an empty theatre. I always had in mind the fact that there were going to be two audience members and that gave me comfort. However, when we did perform, it was very different. Especially considering the vast size of the Parade Theatre. The dance between actors and the audience felt a bit more distant. The energy exchange was virtual and therefore harder to tap into. However, the cast and crew trusted each other, the trajectory of the story and that the audience was watching, both online and somewhere in the theatre. It was different yet invigorating.

Sean Sinclair: I expected it to feel completely empty and strange, and it did! That said, it was comforting to know that I had friends and family watching us live at home. However, it also meant they could rewind the performance … and criticize any missed steps.

Is the feeling of performing in front of an empty house different to rehearsing in front of one?

Daniel Assetta: Whenever I’d rehearsed in an empty theatre in the past, I always knew in the back of my mind that it was an opportunity for the cast and crew to ensure everything was running smoothly. Everyone knew that once an audience came in, there would be a new energy. In the past, I’ve found it’s the response from an audience that really takes a show to the next level, and as performers we crave that feeling. Therefore, it’s definitely a completely different experience.

Ayla Beaufils: Performing somewhere as magnificent as the Parade Theatre is already such a privilege, particularly as a drama student. Therefore, it feels a bit surreal to perform during such a difficult time, when the majority of theatres are closed and many actors and creatives are out of work. I feel deeply grateful to do what I do and to be so supported by NIDA, my fellow cast, the technical crew and creative team. That fuels me every time I step onto the stage or into our rehearsal room. Our show was streamed live so it still felt like we had an audience. The pre-show adrenaline and excitement that I usually feel as I stand in the wings was still there, because I knew we are being watched by a number of cameras throughout the house. However, it does feel different to finish a show and bow to utter silence!

Tim Draxl: Definitely. Regardless of there being no physical audience, you are hyper aware that there are cameras on you and people are watching. I find that a rehearsal is much more clinical – you’re self-critical; you scrupulously pour over every technical detail; and in some ways, it’s void of excessive emotion. In a rehearsal the energy is cycled inward, whereas in a performance it’s projected outward, be it to a physical audience or down the camera. To touch and affect people watching at home, I find you have to work harder and the energy expenditure for the performer is much, much greater.

Albert Mwangi: While rehearsing, you are very much occupied with character discovery, adjustments in direction, and blocking that relates to camera capture, lighting and character shifts. However, during the performances I felt the emptiness usually filled by an audience and I therefore treated the cameras as silent audience members and worked off the energy of my fellow actors. It really worked for Ghost Lights. Our characters were lost and looking for an audience, so having an empty theatre felt new and different for us as actors and as our characters, which was what the show needed.

Sean Sinclair: I have definitely rehearsed in worse auditoriums than the Sydney Opera House! The difference with this performance? Whilst every seat was empty, I knew that anyone from my mum to thousands of people all around the world could be watching.

Did the experience make you reaffirm or re-evaluate your relationship to your audience and how?

Daniel Assetta: For me, it definitely did both. I’ve always known how crucial that relationship is with an audience, especially in a cabaret setting. When sharing personal stories and singing your favourite songs, the audience plays such an important role in creating that intimate atmosphere for the performance. It’s much harder to laugh at your own jokes when there is no one to bounce off. I love to really engage with people and make an audience feel like they are involved in my journey and a part of the show. Performing in front of a camera makes you really miss having those people in the room with you. The next time I perform for a real live audience, I know that I’m going to be emotional and really make the most of it, because I have definitely missed seeing the way music moves people.

Ayla Beaufils: I realised how much I crave the energetic and emotional transaction between an audience and the actor, and that is what I miss about performing live theatre the most. Without an audience, the actors only had each other and the onstage world we’d crafted with the crew, which allowed us a different kind of freedom.

Tim Draxl: It certainly made me more appreciative of the audience in a live-music or cabaret setting. I’m used to the relationship you have with an audience after the event –the delayed response if you like – because of my background in film and television, where you work on something in isolation, present it to an audience and then receive the payoff, that energy transfer, after you’ve done your bit rather than during it. However, it wasn’t until the live stream at the Sydney Opera House that I realized how much I rely on that energy transfer with the audience during a cabaret performance. And I wasn’t prepared for the sheer exhaustion afterwards, or the flood of tears that came when that energy transfer finally happened upon returning to my dressing room andseeing all the beautiful messages from people and colleagues I hadn’t heard from in years. It was very special.

Albert Mwangi: The Ghost Lights experience made me do both. It reaffirmed the strength and presence an audience has in storytelling – the dance of energy between them and the actors on stage. It is both intimidating and exciting to feel those intense moments of utter silence and light hearted moments filled with laughter, especially when it’s a full house. That is what I felt on a micro level with the two audience members, in contrast to the size of the stage. It felt very focused – like tunnel vision – as though we were capturing the audience members’ shifts in energy as fuel for our characters. The re-evaluation of the relationship had to do with the nature of the show and where it worked to not have a full house, but instead stream to the larger audience watching on their devices. I came to treat the cameras as audience members themselves and learnt to imagine and feel the energy of everyone watching as our Ghost Light characters searched for their audience and yearned to justify their own reality.

Sean Sinclair: This experience totally made me reaffirm how vital our relationship with an audience is. The great thing about The Tap Pack is that we treat the audience as another member of the pack, bouncing jokes and gags off them. We feed off purely live energy. It’s something that makes each experience unique and changes from show to show, making every audience so different and special. Of course, that was missing during the live stream, but one of the best parts of being a member of ‘The Pack’ is the camaraderie. When you don’t have an audience, you end up throwing the energy around between the boys on stage.

Can you imagine a future in which there were no live audiences?

Daniel Assetta: Absolutely not. It’s just not the same. I think that as performers in these strange times, we are all finding ways to still spread the joy and share our passion for music to people through online mediums, but nothing compares to live theatre. That feeling of sitting in a darkened auditorium for a night out, watching people pour their hearts and souls into a performance on stage, is just so incredibly special and I think after all of this, people around world are going to desperately need that back in their lives.

Ayla Beaufils: I truly believe there is nothing more magical than watching live theatre, or more cathartic as an actor than to just be with your audience. It’s a feeling you cannot recreate in your everyday, and it’s so addictive, so I don’t see a time when a live theatre audience will be obsolete.

Tim Draxl: The world has changed so drastically, so quickly, and it has brought to light some major inadequacies in our systems. Therefore, I wouldn’t be too surprised if that were to eventuate. I’d be saddened of course, but one thing performers and artists have always been is adaptable – and if not adaptable, then we’ve shown incredible ingenuity and resourcefulness. In fact, we already have, and this experience has shown that online performances are viable. The digital platform has been flung into the spotlight and I think it’s here to stay. It can never replace that feeling of being in front of a live audience; having them bear witness to your journey; and seeing the effect your performance might have on someone right in front of you. However, I’m talking from my own perspective, as someone who has grown up to love it. Perhaps future generations won’t find the same value in that, the way we have. Perhaps they’ll find that connection in some different yet equally beautiful way. That said, I live in hope that we will find a vaccine, and all of this remains purely hypothetical.

Albert Mwangi: I can’t imagine a future without a live audience. I definitely believe that, following the impact of the global pandemic, many more great and creative works will have a lot to do with streaming, but I imagine that live audiences will come back stronger than ever. And there will be plenty of space for both forms of storytelling.

Sean Sinclair: I can, but it’s a bit boring. Live theatre thrives off its unexpectedness and rawness. There is an energy that you can’t replace. A future without that just doesn’t seem right. Like sports is to a sports fan, theatre is to a thespian. |