Podążam za muzyką

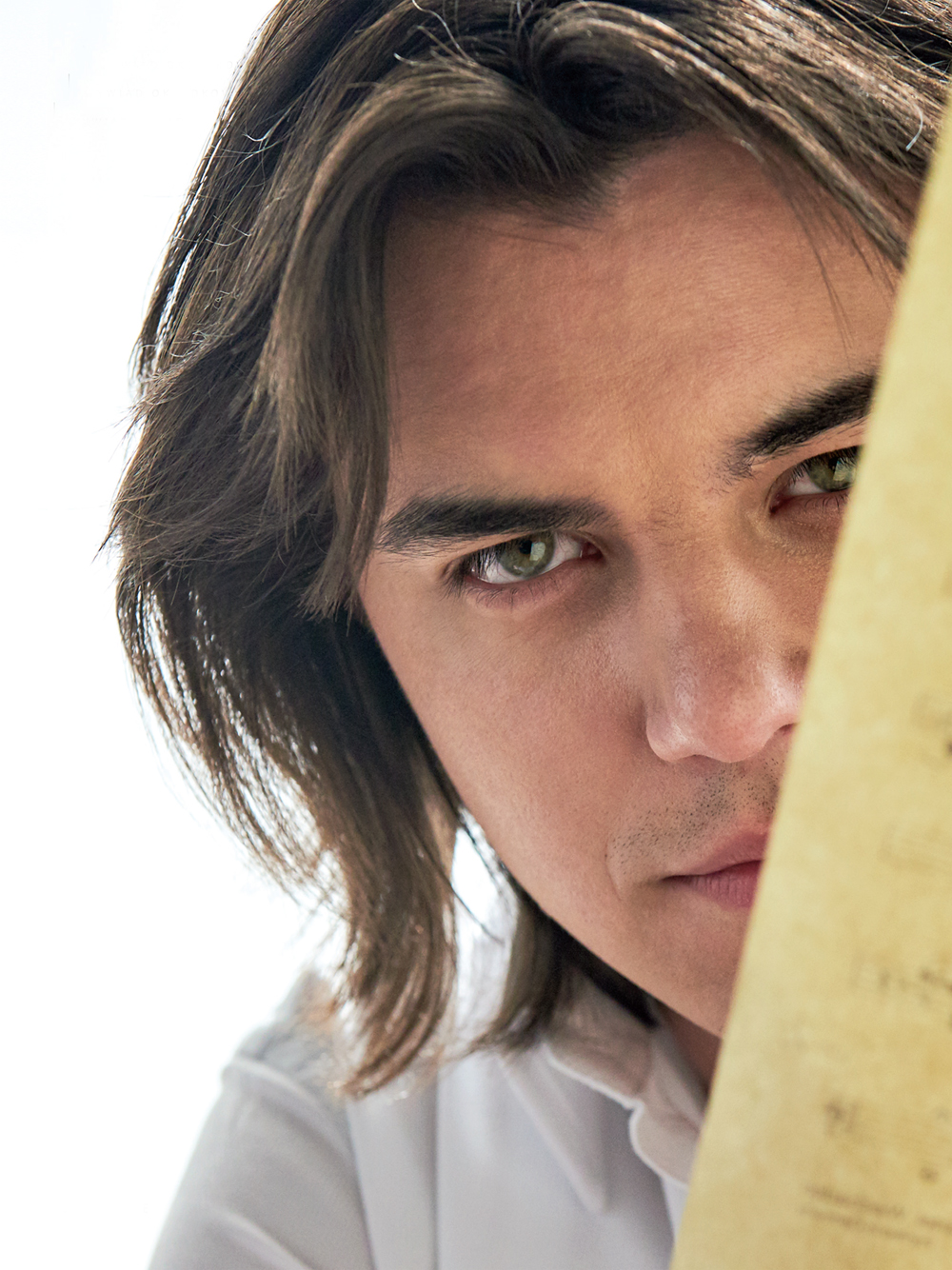

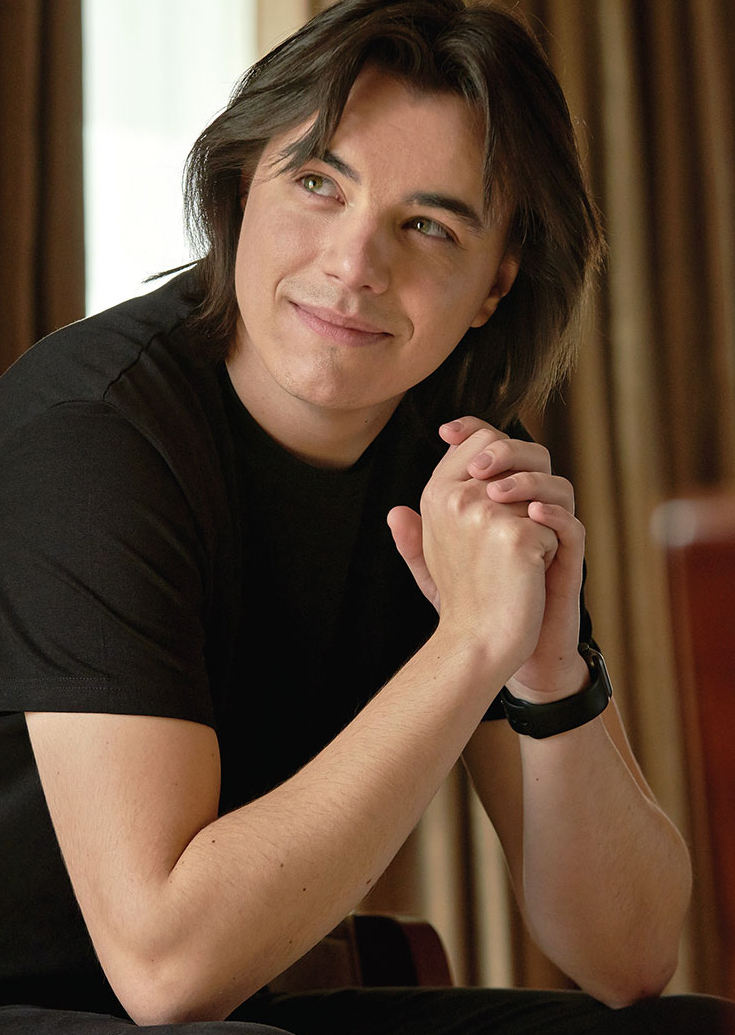

Najważniejszy jest szacunek dla kompozytora i szacunek dla partytury – tego nauczyłem się podczas studiów od mojego profesora – mówi Dawid Runtz, pierwszy dyrygent Polskiej Opery Królewskiej.

TEKST/TEXT: KATARZYNA SKORSKA

ZDJĘCIA/PHOTOS: MICHAŁ ZAGÓRNY

Zawsze chciałam poznać kulisy pracy dyrygenta…

Siadam przy fortepianie, otwieram partyturę, zapoznaję się z utworem, jego budową, instrumentacją. Studiuję też tło historyczne, szczególnie, gdy są to utwory z wcześniejszych epok. Tak przygotowany, gdy opracuję swoją interpretację, przychodzę na pierwszą próbę. Im lepiej poznam utwór, tym pewniej czuję się podczas pracy z orkiestrą.

A na tej pierwszej próbie, co się dzieje?

Zależy ile prób zostało przewidzianych przed koncertem. Bardzo lubię na pierwszej próbie zagrać utwór od początku do końca, aby wszyscy muzycy wiedzieli do jakich temp dążymy, jakie trudności niesie utwór. Po pierwsze staram się wydobyć z partytury wszystko to, co zapisał kompozytor, żeby nie pominąć żadnego szczegółu. Zwłaszcza na pierwszych próbach pilnuję, aby muzycy dokładnie realizowali wszystkie znaki zapisane przez kompozytora. Gdy ten etap pracy jest za nami, wtedy dopiero nabudowuję interpretację. Podstawą dla własnej wizji utworu jest szacunek dla partytury, wszystko musi logicznie wynikać z muzyki, a nie jedynie z własnych upodobań. To dla mnie niezwykle ważne, aby wszystkie elementy znajdujące się w partyturze zaistniały w wykonaniu, ponieważ interpretacja w dużym stopniu opiera się na ustawieniu balansu brzmienia orkiestry, a także uwypukleniu danego elementu. Nad takimi szczegółami pracuje się zazwyczaj na kolejnych próbach. Coraz częściej, zwłaszcza w repertuarze muzyki klasycznej, przygotowuję swój materiał dla orkiestry. Zakupuję w wydawnictwie muzycznym materiał orkiestrowy, czyli partię każdego instrumentu, potem w domu opracowuję smyczkowanie, artykulację, dynamikę, jak również inne wskazówki wykonawcze.

Muzycy dostają te materiały przed pierwszą próbą…

Dostają je zwykle z miesięcznym wyprzedzeniem, po to, by mogli się dobrze z nimi zapoznać.

Czy tego właśnie nauczył cię twój profesor?

Tak, między innymi tego nauczył mnie profesor Antoni Wit. Myślę, że jestem jednym z niewielu dyrygentów, którzy w ten sposób pracują. Taki system wymaga sporego nakładu czasu i środków na zakup materiałów, ale efekt wykonania rekompensuje te trudności. Ponadto jeśli pracuję z inną orkiestrą jako gościnny dyrygent, wysyłam wcześniej opracowany materiał. Dzięki temu zaoszczędzam czas na próbie.

Powiedz proszę, jak to było być uczniem profesora Antoniego Wita?

Miałem ogromne szczęście, że byłem ostatnim studentem profesora Wita. Przez ostatnie dwa lata moich studiów profesor przychodził na uczelnię właściwie tylko dla mnie, przez to poświęcał mi więcej czasu. Zajęcia bywały dłuższe niż wynikało to z grafiku, pracowaliśmy szczegółowo i rzecz jasna mogłem na tym skorzystać. Zdecydowanie na tym zyskałem. Doskonale pamiętam nasze pierwsze spotkanie w Filharmonii Narodowej i wszystkie

pytania jakie zadawał mi profesor: jaka jest moja ulubiona symfonia, od jakiego dźwięku się zaczyna? Profesor zapytał nawet, czy zagrałbym na fortepianie fragment jakiejkolwiek symfonii z pamięci. Wybrałem wstęp do V Symfonii Piotra Czajkowskiego – zresztą ten utwór stanowi bardzo piękną klamrę w mojej edukacji. Od niego zacząłem przesłuchania wstępne u prof. Wita, a na zakończenie studiów poprowadziłem Orkiestrę Filharmonii Narodowej w Warszawie z tą właśnie symfonią.

Czy masz jakąś ładną historyjkę na temat swojej profesji? Na przykład jak to się stało, że zostałeś dyrygentem? Kiedy postanowiłeś, że dyrygentura to jest właśnie to, co chcesz robić?

Myślę, że ta decyzja dość długo dojrzewała we mnie. W szkole muzycznej II stopnia myślałem o kompozycji, właściwie to bardzo chciałem być kompozytorem. Dużo komponowałem i zdobywałem nawet nagrody na konkursach kompozytorskich w Polsce i we Włoszech. Z czasem zaczynałem lepiej poznawać samego siebie i odkrywać pewne predyspozycje, które pozwoliłyby mi zostać dyrygentem. W pewnym momencie uznałem, że kompozycja jest szalenie interesująca i chętnie bym ją studiował, natomiast wizja

współpracy z wieloma innymi artystami, z orkiestrami, chęć bliskiego obcowania ze środowiskiem muzycznym zwyciężyły. Mój dom rodzinny zawsze był przepełniony muzyką, od dziecka ojciec zabierał mnie na próby orkiestry i przyznaję, że postać

dyrygenta zawsze mnie frapowała.

Od najmłodszych lat grasz na…

Fortepian był obecny w moim życiu od zawsze. A dokładniej od chwili, kiedy rodzice kupili instrument, który miał początkowo służyć jako wystrój w domu, a stał się od razu moją „zabawką”. Gdy byłem jeszcze przedszkolakiem, zwyciężyłem w konkursie piosenki, w którym śpiewałem i akompaniowałem sobie, grając na fortepianie.

Ale nigdy nie myślałeś żeby zostać wirtuozem gry na fortepianie?

To rzeczywiście ciekawe, bo właściwie nauczyłem się grać na fortepianie bez korzystania z nut. Po prostu to, co usłyszałem potrafiłem zagrać…

To się chyba nazywa słuch absolutny…

Umiejętność grania ze słuchu bardzo mi pomagała, rozwijała moją wyobraźnię – akurat w tym względzie chyba rzeczywiście zostałem obdarowany. Zawsze lubiłem grać jeden utwór w różnych tonacjach, mój słuch harmoniczny dzięki temu też się rozwijał. Dzisiaj w pracy dyrygenta to wyobrażenie muzyki w głowie pomaga mi bardzo w czytaniu i uczeniu się

partytur.

Uwielbiam i bardzo cenię dyrygentów, którzy dyrygują z pamięci!

Nie ma to większego znaczenia w muzyce. Opery dyryguję z nut, chociaż znam je bardzo dobrze. Jest w nich jednak zbyt wiele elementów, nad którymi muszę panować i które mogą wymagać szybkiej reakcji czy interwencji: orkiestra, śpiewacy, chór, scena. Prawdę mówiąc, na ogół nie potrzebuję partytury podczas koncertów symfonicznych. Nie jest to trudne, wystarczy rzetelnie przeczytać partyturę kilka razy przy fortepianie.

Swoje umiejętności rozwijałeś pod okiem maestro Riccardo Mutiego w Rawennie. Z pewnością wiele też ci dały prestiżowe kursy dyrygenckie prowadzone przez Daniele Gatti z orkiestrą The Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra w Amsterdamie.

Doskonaliłeś się także podczas Festiwalu Tanglewood w Stanach Zjednoczonych, organizowanego przez Boston Symphony Orchestra. Które z tych doświadczeń było dla ciebie najważniejsze?

Każdy dyrygent inaczej pracuje z zespołem. Bardzo miło wspominam doświadczenia z orkiestrą The Royal Concertgebouw w Amsterdamie pod kierunkiem Daniele Gatti, gdyż pokazał on nam nieco inną stronę pracy dyrygenta – bardzo detaliczną

w kształtowaniu brzmienia. Zainspirował mnie i nakłonił do refleksji, jak pracować z orkiestrą nad rodzajem dźwięku, sposobem jego wydobycia, intensywnością, nad jednolitością w grupie, na jak szczegółowe aspekty można zwracać uwagę i je kształtować. Pamiętam, kiedy pierwszy raz stanąłem przed The Royal Concertgebouw z IV Symfonią

Mahlera, uświadomiłem sobie, że nigdy wcześniej nie słyszałem na żywo takiej jakości dźwięku, takiej miękkości, tak wspaniałej reakcji na każdy ruch – to było coś niesamowitego. Warto było uczestniczyć w tych wyjątkowych kursach dla takiej chwili.

Powiedz proszę, jak tacy wytrawni muzycy reagują na bardzo przecież młodego dyrygenta?

Bardzo życzliwie. Z muzykami z orkiestry w Amsterdamie rozmawiałem wielokrotnie podczas tych kursów i otrzymałem od tych artystów mnóstwo bezcennych wskazówek i dobrych rad. To z pewnością bardzo pomaga mi w rozwoju umiejętności. Każe zastanawiać się co w sobie ulepszyć, a co zostawić.

A jak jest z polskimi orkiestrami?

Z najlepszymi polskimi orkiestrami jest podobnie. To są znakomici muzycy, którzy dobrze pamiętają, że również byli młodzi. Odczuwam zazwyczaj z ich strony przyjazne wsparcie.

Spośród doświadczeń, które masz na swoim koncie, które uznałbyś za najtrudniejsze, najbardziej wymagające, stresujące?

Bardzo ważny i bardzo zaskakujący był dla mnie moment, kiedy otworzyłem pocztę mailową i zobaczyłem wiadomość od menadżera Boston Symphony Orchestra z USA z zaproszeniem na przesłuchania na stanowisko asystenta orkiestry. To była duża niespodzianka, tym bardziej, że nie była to odpowiedź na moją aplikację, bo orkiestry tego

formatu same wyszukują sobie kandydatów. Oczywiście poleciałem do Bostonu, prowadziłem III Symfonię Brahmsa i Koncert skrzypcowy Mendelssohna. Nie udało mi się dostać tego stanowiska; spośród czterech kandydatów, którzy tam się znaleźli, wygrał mój kolega z Tajwanu. Ale najważniejsze jest, że wcale nie towarzyszyło mi poczucie smutku, że coś przegrałem. Wręcz przeciwnie, byłem szczęśliwy, że w ogóle miałem zaszczyt stanąć przed jedną z czołowych orkiestr Ameryki. To już jest spełnienie marzeń, a doświadczenia,

które tam zdobyłem, są bezcenne. Niedługo potem otrzymałem zaproszenie na festiwal Tanglewood i dwa tygodnie spędziłem w Massachusetts.

Z każdą orkiestrą można się dogadać? Powiedz proszę, czy nie potrzeba do tego jakiejś szczególnej chemii, porozumienia muzycznych dusz?

Nie wiem jak to się dzieje, ale zdarza się, że od pierwszych chwil, gdy staję za pulpitem dyrygenta, nawiązuję z zespołem bardzo dobry kontakt. Dlaczego i jak – trudno to wytłumaczyć. Bardzo miło wspominam moją ostatnią relację z Zagreb Philharmonic

Orchestra (Narodowa Orkiestra Chorwacji), która zaprosiła mnie w tym roku na tournée po

Kuwejcie, gdzie zagraliśmy serię koncertów. Z obu stron było tak dobre porozumienie, że otrzymałem już kolejne dwa zaproszenia. W styczniu przyszłego roku poprowadzę z tym zespołem między innymi Święto wiosny Igora Strawińskiego. Wykonanie tego utworu to z pewnością wyzwanie zarówno dla dyrygenta jak i muzyków, ale zgoda Orkiestry akurat

na Święto wiosny jest dowodem pewnego zaufania.

A co cię najbardziej podczas koncertu stresuje?

Może nie stresuje, co raczej ekscytuje… Sam fakt występowania na scenie; ekscytuje mnie muzyka, która zaraz będzie rozbrzmiewać. Przecież koncert jest ukoronowaniem wcześniejszej pracy, wszystkich prób z orkiestrą. To kulminacyjny moment, to czas na

pokazanie wszystkiego, co udało nam się wypracować. To jest naprawdę niezwykle ekscytujące.

Na jakie kontuzje narażony jest dyrygent? Co cię najbardziej boli po koncercie – ręce, ramiona?

Bardzo ważna jest postawa. Mogą niekiedy doskwierać bóle pleców. Ostatnio bardzo lubię pływać i staram się, żeby moja kondycja fizyczna szła w parze z kondycją psychiczną.

Nie spotkałam dwóch podobnie poruszających się dyrygentów. Mam na myśli całą tę waszą gestykulację.

To jest z pewnością związane z budową fizyczną, każdy z nas musi odnaleźć się komfortowo w swoim ciele. Niektórzy są bardzo ekspresyjni, inni raczej powściągliwi. Prawdę mówiąc, coraz rzadziej zastanawiam się nad rękami. Gesty dyrygenta

naturalnie muszą odpowiadać muzyce, musimy też pamiętać, by służyły i pomagały orkiestrze w precyzyjnej grze. Im trudniejsze i bardziej skomplikowane fragmenty, tym bardziej upraszczam swój ruch, żeby muzyk miał pełną jasność. Z kolei w lirycznych częściach prowadzę kantylenę – mogę oczywiście zasugerować kierunek frazy, jej intensywność czy stopień dynamiczny. Po prostu podążam za muzyką. Dyrygent powinien zwracać się tam, gdzie właśnie dzieje się coś interesującego i pięknego w muzyce. Bo dyrygowanie to przede wszystkim kształtowanie muzyki, a nie puste gestykulowanie.

A jakie utwory sprawiają ci największą trudność?

Najtrudniejsze w interpretacji są dla mnie utwory dawno minionych epok i myślę, że im bardziej wstecz, tym trudniej. Mozart na przykład jest dość wymagającym kompozytorem wbrew temu, co się czasem słuchaczom wydaje. Symfonie Haydna bywają skomplikowane dla dyrygenta i – wbrew pozorom – o wiele trudniejsze niż muzyka XIX wieku, również

pamięciowo. Nie mówiąc już o muzyce baroku, która jest jeszcze bardziej nieregularna i sprawia różne trudności w interpretacji. Gdyby wziąć partyturę z tamtej epoki, okaże się, że cała dynamika ogranicza się do forte i piano, zresztą podobnie jest z artykulacją. Czy rzeczywiście w tamtych czasach grano w ten sposób? Nie sądzę. Współcześni kompozytorzy nie pozostawiają dużego marginesu na swobodę interpretacyjną, ponieważ każda nuta jest oznaczona, a partytury zaopatrzone są w swoje legendy. Nie ma żadnych nieścisłości czy też niedomówień. Natomiast u kompozytorów minionych epok nuty są „czyste”, a dobór artykulacji, dynamiki, dokładnych temp leży po stronie dyrygenta.

Jak to się stało, że będąc zaledwie dwudziestokilkulatkiem, niemal prosto po studiach zostałeś zaangażowany na stanowisko pierwszego dyrygenta Opery Królewskiej?

Profesor Peryt był jedną z najbardziej niezwykłych i najciekawszych osób jakie w życiu poznałem. Był też człowiekiem, który najbardziej mi pomógł zawodowo. On jako pierwszy zaznaczył mocny punkt na mojej osi czasu, proponując pracę na tak ważnym stanowisku.

Pamiętam, było to dokładnie 6 grudnia 2017 roku, co żartobliwie skwitował, jako prezent na Mikołajki… W jednej z naszych rozmów profesor powiedział, że jego życzeniem jest, by wszyscy znali orkiestrę Dawida Runtza. Chodziło mu o ukazanie rangi misji, którą mi powierzył. To dla mnie duża odpowiedzialność i zarazem piękny gest z jego strony.

Uginasz się pod tym brzemieniem?

Chciałbym, aby orkiestra Polskiej Opery Królewskiej za pewien czas stała się rozpoznawalnym zespołem o wysokiej klasie. Odkąd profesor Ryszard Peryt odszedł od nas, jego słowa pobrzmiewają w mojej głowie coraz mocniej. |

DAWID RUNTZ ukończył w 2016 roku studia w zakresie dyrygentury symfonicznooperowej w klasie Antoniego Wita. Warsztat rozwijał pod kierunkiem Jormy Panuli i Jacka Kaspszyka, a także maestro Riccardo Mutiego. Odbył prestiżowe kursy dyrygenckie prowadzone przez Daniele Gatti, doskonalił umiejętności podczas Festiwalu Tanglewood w Stanach Zjednoczonych, współpracował z Teatrem Wielkim-Operą Narodową w Warszawie. Koncertował m.in. w Japonii, Hongkongu, na Litwie, we Włoszech i w Chorwacji. W 2018 roku zdobył III Nagrodę oraz Nagrodę Publiczności na 1st International Hong Kong Conducting Competition. Piastuje stanowisko pierwszego

dyrygenta Polskiej Opery Królewskiej.

![]()

MUSIC IS MY GUIDE

TEXT: KATARZYNA SKORSKA

PHOTOS: MICHAŁ ZAGÓRNY

The most important thing is respect for the

composer and the score – that’s what I learned

from my professor” says Dawid Runtz, the

principal conductor of the Polish Royal Opera.

I’ve always wanted to learn about the details of a conductor’s job.

I sit down at the piano, open up the score and get acquainted with a piece, its structure and instrumentation. I also study its historical background, especially if it’s from an earlier era. Once that’s done and I’ve worked out my own interpretation, I go to the first rehearsal. The better I get to know a composition, the more confident I feel working with an orchestra.

What happens at the first rehearsal?

It depends how many rehearsals are planned before a concert. At first rehearsal, I really like to play a piece all the way through, from the beginning to the end, so that all musicians know what kind of tempo we’re aiming and what difficulties it presents. First of all, I try to glean everything the composer has written from the score, so that I don’t miss any details. At the first rehearsal, I specifically want to make sure that the musicians accurately follow what the composer wrote. Once that’s complete, I start developing our

interpretation. The basis for one’s own vision of a piece is respect for the score – everything must logically emerge from the music and not just from one’s own preferences. It is extremely important for me that all the elements in the score come into play, because the interpretation is largely based on finding a balance between the orchestra’s sounds and those parts you want to emphasise. Such details are usually worked out at subsequent rehearsals. More and more often, especially with the classical repertoire, I find

I prepare my own material for the orchestra. I buy the individual orchestral parts for each instrument from a music publishing house. Once I’m home, I figure out the bowing, articulation, dynamics, as well as other features of the performance I’m aiming for.

Do the musicians get this material before the first rehearsal?

They usually get it a month in advance, so that they can familiarise themselves with it properly. Is this what your professor taught you? Yes – among the many other things Professor Antoni Wit taught me. I think I am one of the few conductors who work in this way. Such an approach requires a lot of time and resources to purchase the materials, but the results make it all worthwhile. In addition, if I work with another orchestra as a guest

conductor, I send them material I prepared previously in advance. That way, I save rehearsal time.

What was it like to be Professor Antoni Wit’s student?

I was very fortunate to be his last student. During the last two years of my studies, Professor Wit came to the university just for me, hence he gave me more time. Classes were longer than scheduled, we worked in detail and I’ve benefited from that ever since. It definitely paid off. I perfectly remember our first meeting at the National Philharmonic and all the questions the professor asked me: „What’s your favorite symphony?” and „How does it begin?” The professor even asked if I would play a fragment of any symphony on the piano from memory. I chose the introduction to Symphony No. 5 by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. After all, that piece was a major part of my education. From that point I onwards, I started gradually taking lessons with Professor Wit. At the end of my studies, I led the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra with that same symphony.

Can you share an anecdote about your profession? For example, how did you come to be a conductor? Or, when did you decide that you wanted to conduct for a living?

I think that decision was a long time coming. During the 2nd grade of music school, I was thought about composition. In fact, I really wanted to be a composer. I composed a lot and even won prizes at composers’ competitions in Poland and Italy. With time, I began to get to know myself better and discovered some predispositions that enabled me to become a conductor. At some point, I decided that the composition was extremely interesting and that I wanted to study it, but the idea of cooperating with many other artists and orchestras, as well as the desire to closely associate with the music environment won out. My family home has always been full of music. My father took me to orchestral rehearsals

since I was a child and I admit that the character of the conductor has always been fascinating.

From an early age you’ve played …

… the piano has always been present in my life. Ever since my parents bought an instrument that was supposed to serve as a of home decor, and it became my „toy” right away. When I was still a preschooler, I won a song contest in which I sang and accompanied myself playing on the piano.

But you never thought of becoming a virtuoso at the piano?

It’s really interesting, because I actually learned to play the piano without reading sheet music. I just listened to what I what I was supposed to play.

Playing by ear?

Yes, it helped me a lot and broadened my imagination. I was naturally gifted in that regard. I liked switching keys when playing a piece of music and this helped develop my ability to hear harmonic intervals. These skills now help me in my day-to-day work as a conductor, reading and learning scores.

I have a lot of respect for conductors who can conduct from memory.

It makes little difference in music. I usually conduct opera with the score in front of me, even if I know it very well. There are too many elements I need to control, which can require a quick reaction or intervention: the orchestra, the singers, the choir and staging. To tell you the truth, I don’t usually need a score during symphonic concerts. I don’t find it

that hard and I usually just need to have read through the score a few times at the piano.

You’ve honed your skills under the supervision of Maestro Riccardo Muti in Ravenna, by attending prestigious courses conducted by Daniele Gatti at the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam and during the Tanglewood Festival in the United States, organized by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Which of these experiences was the most important?

Each conductor works differently. I really remember my experience at the Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam under the direction of Daniele Gatti, because he showed us a slightly different side to a conductor’s work; a highly detailed method of shaping sound. He inspired me and made me reflect on how I work with an orchestra on achieving a particular sound, the way it is drawn out, the intensity, uniformity across the ensemble, how to draw attention to certain aspects of a piece and shape them. I remember when I first stood before the Royal Concertgebouw with Mahler’s Fourth Symphony and I realized that I had never heard such sound quality, such softness, such a great reaction to my every move. It was amazing and worth participating in those special courses for that very moment.

How did such experienced musicians react to a young conductor?

Very kindly. I talked to the musicians in Amsterdam many times during those courses and I received many invaluable tips and good advice from them. It certainly has helped me develop my skills and made me assess what is good enough or still needs to be improved.

And what is it like working with Polish orchestras?

It’s the same with the best Polish orchestras. They employ excellent musicians who haven’t forgotten what it is to be young. I usually find them very friendly and supportive.

Of all your experiences you have on your account so far, which would you consider the most difficult, the most demanding and stressful?

A very important and very surprising moment for me was when I opened up my e-mail and saw a message from the manager of the Boston Symphony Orchestra inviting me to audition for the position of the orchestra’s assistant conductor. It was a big surprise, because hadn’t applied for the job. Orchestras of that calibre usually know who they want. Of course, I flew to Boston and conducted Brahms’ Symphony No. 3 and Mendelssohn’s

violin concerto. I didn’t get the job. There were four candidates in total and my colleague from Taiwan was successful. However, the most important thing was that I wasn’t sad. On the contrary, I was happy that I’d had the honour of standing in front of one of America’s leading orchestras. That was a dream come true, and the experience was invaluable. Soon

after, I received an invitation to the Tanglewood festival and spent two weeks in Massachusetts.

Do you get along with every orchestra? Does it take a special kind of chemistry or mutual understanding of spirit of the music?

I don’t know how it happens, but from the very first moment I stand at the conductor’s podium, I establish a rapport with a orchestra. Why and how is difficult to explain. I have very fond memories of my recent experience with the Zagreb Philharmonic (National Orchestra of Croatia). This year I was invited to tour Kuwait with them and we played

a series of concerts. We got on so well that I now have two return engagements, including Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring next January. Performing this piece is always a challenge for both the conductor and the musicians, but their decision to ask me to conduct The Rite of Spring attests to their confidence in me.

What is the most stressful thing during a concert?

It’s not a question of stress, but rather excitement. The very fact that I’m on stage, and that a piece of music is about to be heard, excites me. After all, the concert is the culmination of so much preparation and rehearsals with an orchestra. It’s the climax – the moment we must reveal what we’ve been working on. It’s extremely exciting.

What kind of injuries is a conductor prone to? What hurts the most after a concert? The hands, the arms?

Posture is very important and can often help overcome back pain. Recently, I’ve been swimming a lot and I try to look after both my physical and mental condition.

I haven’t come across another conductor as physically expressive as you.

That probably has a lot to do with my physical make-up. We all have to know our bodies. Some conductors are very expressive, while others are more restrained. In truth, I rarely think about my hands. A conductor’s gestures must naturally correspond to the music and we must also remember to serve and help the orchestra in achieving a precise performance. The more difficult and complex the fragments, the more I simplify my movements to make it clear for musicians. The more lyrical the part, the more lyrical I become and I can, of course, suggest the phrasing, its intensity or dynamic. I just follow music. A conductor should be lead by what’s interesting and beautiful in the music. Conducting is about shaping music and not empty gestures.

Which pieces present are the most challenging for you?

Older works are more challenging to interpret. The further into the past you go, the harder they become. Take Mozart for example. He is quite a demanding composer despite what listeneres may think. Haydn’s symphonies can be complicated for the conductor and – contrary to popular belief – much more difficult than the music of the nineteenth century. His works are also hard to memorise. Not to mention Baroque music, which is even more irregular and causes many challenges in interpretation. If you were to take a score from that era, it turns out that all the dynamics are limited to forte and piano. Likewise with articulation. Did they really play that way in those days? I don’t think so. Contemporary composers leave little room for interpretation. Each note and scores is already marked up. There are no inaccuracies or misunderstandings. On the other hand, the notes of

a composer from a bygone era is „pure”, and it is up to the conductor to determine the articulation, dynamics and precise tempo.

How did it come about that you – a mere twenty-something straight after graduation – were appointed principal conductor of the Polish Royal Opera?

Professor Peryt was one of the most amazing and interesting people I’d ever met. He wasa the one who also helped me the most professionally. He was the first to leave a strong mark on my career, by proposing that I take up the position. I remember it was December 6, 2017. He jokingly remarked that it was a St. Nicholas’ Day present. He once told me it was his wish that everyone would come to know it as the Dawid Runtz Orchestra. He wanted people to appreciate what he’d entrusted to me. It is huge responsibility for me and a beautiful gesture on his part.

How are you facing up to the challenge?

I would like the Orchestra of the Polish Royal Opera to be recognized as first-class. Ever since Professor Ryszard Peryt left us, his words have echoed louder and louder in my mind.

DAWID RUNTZ graduated in 2016 in the field of symphony and opera conducting, having studied under Antoni Wit. He attended workshops under the direction of Jorma Panuli and Jacek Kaspszyk, as well as maestro Riccardo Muti. He also took part in prestigious conducting courses led by Daniele Gatti and he honed his skills further at the Tanglewood Festival in the United States. He has collaborated with the National Opera at the Grand Theater in Warsaw and he has performed, among others, in Japan, Hong Kong, Lithuania, Italy and Croatia. In 2018 he won the 3rd Prize and the Audience Prize at the 1st International Hong Kong Conducting Competition.|