Wszyscy kochają Antypody. Dwoje artystów z tego regionu podbija świat wystawami w Paryżu i Singapurze. Żydówka i muzułmanin. Oboje są Australijczykami, którzy kwestionują globalny strach przed migrantami i udowadniają, że różnorodność wnosi do naszego życia bardzo potrzebny koloryt. Spotykamy się z Jo Meisner i Abdulem Abdullahem podczas przygotowań do ich wernisaży.

Tekst: Jansson J. Antmann

Jo Meisner, self portrait

Na pierwszy rzut oka dzieła sztuki Jo Meisner przypominają szkice kostiumów autorstwa Léona Baksta. Po bliższym przyjrzeniu się z czarno-białego tła wyłaniają się paryskie ulice. Ożywiają je kolory afrykańskich tkanin, takich jakie kiedyś przywożono z Holandii. Artystka, która jest potomkiem żydowskich imigrantów z Polski, swoją pierwszą wystawą w Paryżu pod tytułem „Tożsamość” ukazuje sytuację przesiedleńców na całym świecie. Metaforą izolacji jest usunięcie ich sylwetek z otaczającego tła i zastąpienie ich barwnymi plamami przywodzącymi na myśl dziedzictwo kolonialne. Technika Meisner polega na mocowaniu tkaniny na pleksi i stanowi podprogowe odniesienie do pięknych witraży synagogi, którą uwielbiała jako dziecko.

Jo Meisner, Light and darkness (2017) Digital print on laser cut perspex, 19 x 13 x 4 cm

„Moje prace oscylują w obszarze fotografii, instalacji i rzeźby oraz starają się zgłębić współczesne pojęcie tożsamości. Tłum i człowiek to tematy mojej twórczości, która w różny sposób koncentruje się na kulturowym i społecznym wpływie wymuszonej migracji na tkankę indywidualnej psychiki” – mówi Meisner. „Moja twórczość odnosi się do historii malarstwa figuratywnego, a także tradycji fotografii ulicznej i historii produkcji tekstyliów. Opatulanie, spinanie i opakowywanie są kluczowe w mojej pracy i przywołują na myśl akt „macierzyństwa” w rozwoju człowieka.”

Jo Meisner, Strange Dolls II (2017- 2018) Stitched fabric and paper on Perspex, 30.5 x 43 x 8 cm

Jo Meisner, Displaced (2017) Digital print on laser cut perspex, 28 x 12.5 cm

Kolejna część wystawy przedstawia tłum w stanie przejściowym, charakteryzujący się przedstawieniem anonimowych postaci widzianych z boku i z tyłu. To temat niezwykle ważny dla artystki.

„Ludzie są wyizolowani z kontekstu tłumu i zostają zastąpieni przez lustra, cienie i reliefy. W ten sposób postać staje się substytutem psychologicznej introspekcji i samoidentyfikacji, a moją pracę można odczytać jako autoportret”.

Jo Meisner, Eternal Movement (2017) Digital print on laser cut perspex, 28 x 12.5 cm

Jo Meisner, Eternal Movement (2017) Digital print on duraclears, metal bar, 200 x 127 cm

Zdjęcie jest punktem wyjścia dla wielu prac Meisner, podobnie jak szkic malarski. Mówi: „W mojej pracy angażuję się w sprawy codzienne i chociaż fotografuję, nie myślę o sobie, że jestem fotografką, ale raczej kolekcjonerką zdjęć. Fotografie nie tylko pojawiają się w moich pracach plastycznych, ale także są jak rysunki w szkicowniku będąc istotną dokumentacją mojej sztuki. Dla mnie proces tworzenia jest równie ważny jak końcowe dzieło.”

Abdul Abdullah in front of his artwork, You can call me naïve (2018) Manual embroidery

Abdul Abdullah in front of his artwork, You can call me naïve (2018) Manual embroidery

made with the assistance of DGTMB studios. 150cm x 120cm, Fot. Jansson Antmann

Podobnie jak w przypadku Meisner, prace fotograficzne Abdula Abdullaha przyniosły mu sławę, ale artysta pracuje również w innych obszarach, co widać na jego ostatniej wystawie indywidualnej w Singapurze, zatytułowanej ‘Jangan Sakiti Hatiku – Nie łam mojego serca’. Inspirację swoich dzieł Abdullah czerpie z kultury popularnej. Mówiąc o swojej własnej ścieżce kariery, używa cytatu Buzz’a Lightyeara z filmu „Toy Story”, „Nie lecę, ale upadam ze stylem”.

W czasach mrocznej i często ofensywnej retoryki politycznej Abdullah chce się uśmiechać. „Moim zamiarem jest utrzymanie poczucia humoru. Muszę cieszyć się moją pracą i chcę, żeby inni też się nią cieszyli. To żadna propaganda. Niektórzy krytykują moje prace za to, że nie są wystarczająco bezpośrednie, ale czuję, że znaczenie mojej pracy ucierpiałoby, gdyby tak było. Nie mogę przekonywać krzycząc. To jest moja osobista wrażliwość. Byłbym okropnym dziennikarzem”. Abdullah studiował dziennikarstwo, zanim został artystą. Szczodrze obdarza nas swoją sztuką i chce, aby ludzie byli przez nią wzbogacani. „Moje dzieło może rzucić wyzwanie widzom, ale nie powinno ich karać. Nie chcę przeciągać kogoś przez błoto, żeby przekazać wiadomość. Chcę, żeby ludzie postrzegali to bardziej jako zaproszenie lub ofertę, a ta oferta wciąż może być zabawna.”

Abdul Abdullah, May all your dreams come true (2018) Oil on linen. 240cm x 180cm

I jest zabawna. Uśmiechnięte emotikony są namalowane na tkanych portretach i obrazach wybuchów przypominające dzieła Jamesa Rosenquista lub Roya Lichtensteina. Temat jest ponury, ale dowcipny. Podobnie jak jego brat, Abdul-Rahman, Abdullah jest jednym z niewielu australijskich artystów, którzy z powodzeniem łączą swoją tradycyjną kulturę z wieloma innymi, często borykając się z przeciwnościami.

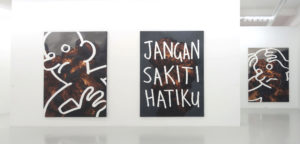

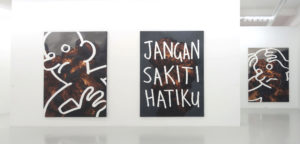

Abdul Abdullah, JANGAN SAKITI HATIKU – Don’t break my heart, 2018

Installation view at Yavuz Gallery Singapore. Fot. Steffanie Relucio

„Nigdy nie czułem się zobowiązany do popierania religii poprzez moją pracę artystyczną, i szczerze mówiąc, spotkałem się z tego powodu z pewną falą krytyki ze strony niektórych członków społeczności muzułmańskiej. Może nie jestem bardzo altruistyczny, a może po prostu nie obchodzi mnie ten aspekt rzeczy. Nie chcę, by myślano, że lekceważę ten temat, po prostu postrzegam to jako kolejną część mojego doświadczenia kulturowego. Moja przeszłość wpływa na moją twórczość w taki sam sposób, w jaki robi to każde wychowanie. Dało mi to fundamenty, na których się opieram i, mam nadzieję, mam coś do powiedzenia. Ostatnio staram się wzbogacić język mojej twórczości i usunąć konkretne odniesienia kulturowe, aby stała się bardziej uniwersalna. Jestem artystą, a nie „artystą muzułmańskim”. Nie tworzę „sztuki islamu”. Chcę, aby międzynarodowa publiczność identyfikowała się z moją pracą, niezależnie od pochodzenia. Ani mój brat, ani ja nigdy nie czuliśmy się związani z żadną konkretną kulturą czy praktyką artystyczną.”

Abdul Abdullah, Delegated Risk Management (2017) Archival print. 100cm x 154cm

Istnieje poczucie ciągłości pomiędzy ich twórczością a dziełami takich artystów jak Marcel Duchamp, Jeff Koons czy David LaChapelle. Przykładem jest seria fotografii Abdullaha z 2017 roku, w tym ‘Delegowane zarządzanie ryzykiem’ i ‘Wzajemne zapewnienia’. Przypominając złożone kompozycje Davida LaChappelle, są one grą z podstępem. Abdullah stara się uchwycić moment, w którym modele tracą koncentrację i sprawdzają wiadomości na swoich telefonach lub patrzą w inną stronę. Tam, gdzie LaChappelle zdaje się kwestionować odrodzenie powierzchowności odbioru, Abdullah odwołuje się do popkultury i science fiction w jeszcze bardziej bardziej wywrotowy sposób, jak w swoim autoportrecie „Podróż na Zachód”. Nie da się uniknąć odczucia dyskomfortu, gdy widzimy go w masce małpy z filmu „Planeta małp” Tima Burtona z 2001 roku. Abdullah jednak chce, abyśmy pamiętali o każdej negatywnej konotacji.

Abdul Abdullah, Journey to the West (2017) Archival print. 75cm x 130cm

Scenariusz horroru z migrantem jako potworem jest tematem prac Abdullaha. „Opiera się na idei, o której czytałem, gdzie Dracula reprezentował semickich Ottomanów w gotyckiej Anglii. Istnieją korelacje między tym „potwornym innym” a wyobrażeniami dzisiejszego migranta, uchodźcy lub „najeźdźcy”. Po raz pierwszy użyłem maski małpy w serialu zatytułowanym „Oblężenie”. Pomysł pojawił się, gdy oglądałem oryginalną wersję „Planety małp” z 1968 roku na moim laptopie. W tle migotały na telewizorze wiadomości 24-godzinnego kanału informacyjnego i kiedy spojrzałem na telewizor, ujrzałem materiał przedstawiający mudżahedinów jadących konno przez pustynię podczas sowieckiej inwazji na Afganistan. Równocześnie na moim laptopie małpy jeździły konno z karabinami. Wpadłem na pomysł wykorzystania maski do oznaczenia sposobu percepcji i jednoczesnego wyobrażenia „potwornego innego” i jego korelacji z moimi doświadczeniami z dorastania w Australii.”

Abdul Abdullah, We are the ones that look back from the abyss (2014) Archival print. 110cm x 120cm

Abdullah jest otwarty na rozpoczęcie dialogu poprzez swoją twórczość. „Staram się zachęcać ludzi do tego, by pozwolili innym na specyficzność i złożoność, jakiej sami sobie życzą. Dzięki mojej pracy zastawiam dla nich pułapkę z jak największymi możliwymi punktami dostępowymi, czy to historycznymi, filozoficznymi, teoretycznymi, czy po prostu estetycznymi, aby skłonić ich do rozmowy, której inaczej by nie prowadzili.”

Abdul Abdullah, Mutual Assurances (2017) Archival print. 100cm x 232cm

Ich metody mogą się różnić, jednak Meisner i Abdullah łączą podobieństwa tematyki i wiara w ludzkość. Przede wszystkim udowadniają oni, że wciąż istnieje jednocząca moc sztuki.

Jo Meisner, Alone together (2016)

Jo Meisner, Alone together (2016)

(Detail) 200 x 762 cm

6 of 8 (each panel 200 x 127 cm)

Digital print on duraclear and aluminium

Jo Meisner – „Identité” (Tożsamość), Facettes BC przy 80 rue de Turenne 75004, Le Marais, Paryż.

Abdul Abdullah – „Jangan Sakiti Hatiku” (Nie łam mojego serca), Galeria Yavuz, Gillman Barracks, 9 Lock Road # 02-23, Singapur 108937.

![]()

The Antipodeans are coming!

Text: Jansson J. Antmann

Everyone loves the Antipodes and two artists from that region are taking the world by storm with exhibitions in Paris and Singapore. One has a Jewish background, the other Muslim. Both are Australians questioning the global fear of the migrant and proving that diversity brings much needed colour to our lives. We meet Jo Meisner and Abdul Abdullah as they prepare for their respective openings.

Jo Meisner, self portrait

At first reminiscent of Léon Bakst’s costume sketches, upon closer examination the black and white backgrounds reveal Parisian street scenes brought to life by the splashes of colour of African textiles, originally imported from Holland. In her first Paris solo exhibition ‘Identité’, Jo Meisner, a descendent of Jewish immigrants from Poland, highlights the plight of displaced peoples around the world. Isolation is represented by the removal of their silhouettes from the world around them, replaced by the bright traces of a colonial legacy. Meisner’s technique of mounting fabric onto Perspex is a subliminal reference to the beautiful stained-glass windows of the synagogue, which she adored as a child.

Jo Meisner, Light and darkness (2017) Digital print on laser cut perspex, 19 x 13 x 4 cm

“My practice spans photography, installation and sculptural assemblage and probes contemporary notions of identity. The Crowd and the Individual are two concepts that I return to as subjects in my work, which has variously focused on the cultural and social impact of forced migration and the fabric of the individual psyche,” says Meisner. “My work playfully aligns itself with the history of figurative painting as well as the traditions of street photography and the history of textile manufacture. Processes of swaddling, pinning and wrapping are central to my practice and are material concerns that recall the act of ‘mothering’ in the development of the individual.”

Jo Meisner, Strange Dolls II (2017- 2018) Stitched fabric and paper on Perspex, 30.5 x 43 x 8 cm

Jo Meisner, Displaced (2017) Digital print on laser cut perspex, 28 x 12.5 cm

Another part of the exhibition presents a subject important to the artist, the crowd in transit, characterised by the representation of anonymous figures seen from the side and behind.

“From the context of the crowd, individuals are isolated and replaced by mirrors, shadows and tactile reliefs; in this way the figure becomes a surrogate for psychological introspection and self-identification and my work could be read as a means of oblique self-portraiture.”

Jo Meisner, Eternal Movement (2017) Digital print on laser cut perspex, 28 x 12.5 cm

Jo Meisner, Eternal Movement (2017) Digital print on duraclears, metal bar, 200 x 127 cm

The photograph is the starting point for much of Meisner’s work, much like a painter’s sketch. As she puts it, “In my work, I am engaging with the everyday and although I take photographs, I do not consider myself a photographer, more ‘a collector of pictures’. These photographs, as well as featuring in the work itself, are in essence drawings in a sketchbook and are a vital documentary of my art. For me, the process is as important as the finished work”

Abdul Abdullah in front of his artwork, You can call me naïve (2018) Manual embroidery

Abdul Abdullah in front of his artwork, You can call me naïve (2018) Manual embroidery

made with the assistance of DGTMB studios. 150cm x 120cm, Fot. Jansson Antmann

Like Meisner, Abdul Abdullah’s photographic work has gained him quite a reputation, but he too works outside that medium, as is evident in his latest solo exhibition in Singapore, ‘Jangan Sakiti Hatiku – Don’t Break My Heart’. Abdullah’s references are rooted in popular culture. In talking about his own career trajectory, he coins a Buzz Lightyear quote from ‘Toy Story’, “I’m not flying, I’m falling with style.”

At a time of dark and often offensive political rhetoric, Abdullah wants to keep smiling. “My intention is to maintain a sense of humour. I have to enjoy my work and I want others to enjoy it too. It’s not propaganda. Some people criticise my work for not being forthright enough, but I feel that the message would suffer if it was. I can’t be persuasive by yelling. That’s my personal sensibility. I’d make a terrible journalist.” Abdullah studied journalism prior to becoming an artist. He is generous with his art and wants people to be rewarded by it. “It can be challenging, but it shouldn’t be punishing. I don’t want to drag someone through the mud to get a message across. I want them to see it more as an invitation or an offering, and that offering can still be fun.”

Abdul Abdullah, May all your dreams come true (2018) Oil on linen. 240cm x 180cm

Fun it is, with Abdullah’s signature ‘smiley’ emoji and similar iconography emblazoned across painstakingly woven portraits and paintings of explosions that recall the works of James Rosenquist or Roy Lichtenstein. The message is dark yet witty. Like his brother, Abdul-Rahman, Abdullah is one of several Australian artists who successfully synergise their traditional culture with those of many others, often in the face of adversity.

Abdul Abdullah, JANGAN SAKITI HATIKU – Don’t break my heart, 2018

Installation view at Yavuz Gallery Singapore. Fot. Steffanie Relucio

“I’ve never felt obligated to advocate my own religion through my work and, frankly, I’ve earned some criticism from certain elements within the Muslim community because of that. Maybe I’m not very altruistic, or maybe I just don’t give a damn about that side of things. Without wanting to sound dismissive, I simply see it as another part of my cultural experience. My background informs my practice in the same way that anybody’s upbringing does. It has given me a platform to stand and, when I do, I hopefully have something articulate to say. Recently I’ve been trying to expand the language of my work and remove specific domestic signifiers so that it’s more accessible. I’m an artist, not a 'Muslim artist’. I don’t make ‘Islamic art’. I want international audiences to connect with my work, regardless of their background. Neither my brother nor I have ever felt tied to any specific culture or practice.”

Abdul Abdullah, Delegated Risk Management (2017) Archival print. 100cm x 154cm

There is a sense of continuity between their work and the likes of Marcel Duchamp, Koons and even LaChapelle. A case in point is Abdullah’s 2017 series of photographs including ‘Delegated Risk Management’ and ‘Mutual Assurances’. Reminiscent of David LaChappelle’s complex compositions, they are an exercise in contrivance. Abdullah exposes this by capturing moments when the models lose focus and check messages on their phones or look the other way. Where LaChappelle seems to question the superficiality of a consumer renaissance, Abdullah references pop-culture and science fiction in an altogether more subversive way, as in his self-portrait 'Journey to the West’. There is no mistaking the overt sense of discomfort he awakens by wearing an ape mask from Tim Burton’s 2001 film, “Planet of the Apes”. Every negative connotation applies and is intended.

Abdul Abdullah, Journey to the West (2017) Archival print. 75cm x 130cm

The horror movie scenario with the migrant as monster is a theme that runs through Abdullah’s work. “It draws on an idea I read about, where Dracula represented a Semitic Ottoman in Gothic England. There are correlations between that ‘monstrous other’ and depictions of today’s migrant or ‘invader’. I used the monkey mask for the first time in a series called ‘Siege’. The genesis for that idea came about when I was watching the original 1968 version of ‘Planet of the Apes’ on my laptop. A 24-hour news channel was on TV in the background and when I looked up, by pure chance, I saw footage of the mujahideen riding on horseback across the desert during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In parallel, the ‘bad guys’ – the apes – were also riding on horseback across my laptop screen, bearing arms. It motivated me to use the mask as a signifier of both the perception and depiction of the ‘monstrous other’ and its correlation to my own experience growing up in Australia.”

Abdul Abdullah, We are the ones that look back from the abyss (2014) Archival print. 110cm x 120cm

Abdullah is optimistic about opening up a dialogue through his work. “I’m trying to encourage people to afford others the specificity and complexity that they afford themselves. Through my work I set a fish-trap for them, embedding as many access points as possible, be they historical, philosophical, theoretical, or simply aesthetic, to draw someone into a conversation they otherwise wouldn’t be having.”

Abdul Abdullah, Mutual Assurances (2017) Archival print. 100cm x 232cm

Their practices may be different, however Meisner and Abdullah are bound by commonalities in their subject matter and their belief in humanity. Above all, they prove that the unifying force of art is very much alive.

Jo Meisner, Alone together (2016)

Jo Meisner, Alone together (2016)

(Detail) 200 x 762 cm

6 of 8 (each panel 200 x 127 cm)

Digital print on duraclear and aluminium

Jo Meisner – ‘Identity’ is presented by Facettes BC at 80 rue de Turenne 75004, Le Marais, Paris.

Abdul Abdullah – ‘Jangan Sakiti Hatiku – Don’t Break My Heart’ is presented by Yavuz Gallery at the Gillman Barracks, 9 Lock Road #02-23, Singapore 108937.

Współczesne dramaty

Współczesne dramaty Present-day dramas

Present-day dramas